San Francisco History 1865-1900

San Francisco History 1865-1900

1888 Biography of Henry George

Preface to 4th Edition, by Henry George

Kearney Agitation in California, by Henry George — 1880

San

Francisco’s Early Labor History

The

Museum’s Labor Archives

John

Swett and Early Calif. Education

Biography

of Andrew Hallidie - Cable Car Inventor

|

THE

KEARNEY AGITATION IN CALIFORNIA.

BY HENRY GEORGE.

Although

something has been done toward the scientific treatment of history and

of the larger facts of sociology, the conception of the reign of law amid

human actions lags far behind the recognition of law in the material universe,

and the disposition to ascribe social phenomena to special causes is yet

almost as common as it is in the infancy of knowledge so to explain phenomena. Although

something has been done toward the scientific treatment of history and

of the larger facts of sociology, the conception of the reign of law amid

human actions lags far behind the recognition of law in the material universe,

and the disposition to ascribe social phenomena to special causes is yet

almost as common as it is in the infancy of knowledge so to explain phenomena.

We no longer

attribute an eclipse to a malevolent dragon; when a blight falls on our

vines, or a murrian on our cattle, we set to work with microscope and chemical

tests, instead of imputing it to the anger of a supernatural power; we

have begun to trace the winds and foretell the weather, instead of seeing

in their changes the designs of Providence or the work of witch or warlock.

Yet as to social phenomena, infantile explanations similar to those we

have thus discarded still largely suffice. One has but to read our newspapers,

to attend political meetings, or to listen to common talk, to see that

very many people, who have in large measure risen to scientific conceptions

of the linked sequence of the material universe, have not yet, in their

views of social facts and movements, got past the idea of the little child

who, if shown a picture of battle or siege, will insist on being told which

are the gold and which the bad men.

As the conductors

of this magazine evidently realize the importance of popularizing in their

applications to social questions the scientific spirit and scientific method,

which in other departments have achieved such wonders, I propose in this

paper to say something of a series of events in California that has attracted

much attention. In an article such as this, I can, however, do little more

than correct some misapprehensions and put the main facts in such relations

that their bearing may be seen. Much that would conduce to complete intelligibility

must, from the limit of space, be omitted.

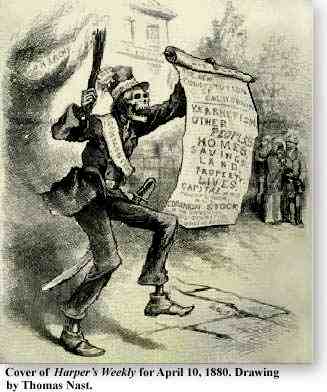

What seems

to be the general idea of these events is well suggested by one of [Thomas]

Nast’s cartoons—a hideous figure, girt with revolver and sword, broadly

badged as “communists,” brandishing in one hand the torch of anarchy, and

in the other exhibiting a scroll on which is inscribed: “Mob Law. The New

Constitution of California. Kearneyism. Other people’s homes, savings,

land, property, lives, capital and honest labor, all common stock in the

universal coöperative brotherhood.” In the distance a group of workmen

stand idle and cowering, while underneath is the device, “Constant Vigilance

(Committee) is the price of liberty in San Francisco.” What seems

to be the general idea of these events is well suggested by one of [Thomas]

Nast’s cartoons—a hideous figure, girt with revolver and sword, broadly

badged as “communists,” brandishing in one hand the torch of anarchy, and

in the other exhibiting a scroll on which is inscribed: “Mob Law. The New

Constitution of California. Kearneyism. Other people’s homes, savings,

land, property, lives, capital and honest labor, all common stock in the

universal coöperative brotherhood.” In the distance a group of workmen

stand idle and cowering, while underneath is the device, “Constant Vigilance

(Committee) is the price of liberty in San Francisco.”

While such

ideas are but exaggerated reflections of the utterances of San Francisco

papers, they are wide of the truth. There has not been in San Francisco

any outbreak of “foreign communism,” nor yet has there been in the workingman’s

movement, or in its results, anything socialistic or agrarian. This movement

has in reality been inspired by ordinary political aims, and what has been

going on in California derives its real interest from its relation to general

facts and its illustration of general tendencies.

While there

has been much in these events to recall to the cool observer the saying

of Carlyle, “There are twenty-eight millions of people in Great Britain,

mostly fools,” it is yet a mistake to regard California as a community

widely differing from more Eastern States. I am, in fact, inclined rather

to look upon California as a typical American State, and San Francisco

as a typical American city. It would be difficult to name any State that

in resources, climate, and industries comes nearer to representing the

whole Union, while, as all the other states have contributed to her population

in something like relative proportions, general American characteristics

remain, as local peculiarities are in the attrition worn off.

There is,

of course, a greater mobility of society than in older communities, and

this may give rise to certain excitability and fickleness. But, everywhere,

the mobility of population increases with the relative growth of cities

and increases the facilities of movement. And, in fact, the newness and

plasticity of society in such a State as California permits general tendencies

to show themselves more quickly than in older sections, just as in the

younger and more flexible parts of the tree the direction of the wind is

most easily seen.

Though yet

comparatively a small city, San Francisco is in character more metropolitan

than any other American city except New York, and is, to the territory

and population of which she is in the commercial, industrial, financial,

and political center, even more of a center than is New York. San Francisco

has no rival. For long distances her bay is spoken of as “the bay,” and

she is not merely the greatest city, but “the city.”

And, though

the European element is largely represented in San Francisco, it is, I

am inclined to think, more thoroughly Americanized than in the Eastern

cities. The reason I take to be, not merely that is drawn from the more

activity and intelligent of the immigration that sets upon the Atlantic

shore, and has generally only reached California after a longer or shorter

sojourn in more Eastern States, but also that the American population having

been drawn from all sections of the country, and from the early days the

whole immigration having been rather of individuals than of colonies or

families, the admixture has been more thorough, and except as to the Chinese,

that polarization which divides a mixed population into distinct communities

has not so readily taken place.

Contrary,

too, to the reputation which she seems to have got, San Francisco is really

an orderly city. Although the police force has been doubled within the

past two years, it still bears a smaller proportion to population than

in other large cities. Chinamen go about the streets with far more security

than I imagine they will go about any Eastern city when they become proportionately

numerous; and, after all said of hoodlumism, there is little obtrusive

rowdyism and few street fights—a fact which may in part result from the

once universal practice of carrying arms.

Nor has

communism or socialism (understanding by these terms the desire for fundamental

social changes) made, up to this time, much progress in California, for

the presence of the Chinese has largely engrossed the attention of the

laboring classes, offering what has seemed to make a sufficient explanation

of the fall of wages and the difficulty of finding employment. Only the

more thoughtful have heeded the fact that in other parts of the world where

there are no Chinamen the condition of the laboring classes is even worse

in California. With the masses the obvious evils of Chinese competition

have excluded all thought of anything else. And in this anti-Chinese feeling

there is, of course, nothing that can properly be deemed socialistic or

communistic. On the contrary, socialists and communists are more tolerant

of the Chinese than any other class of those who feel or are threatened

by their competition. For not only is there, at the bottom of what is called

socialism and communism, the great idea of equality and brotherhood of

men, but they who look to changes in the fundamental institutions of society

as the only means of improving the condition of the masses necessarily

regard Chinese immigration as a minor evil, if in a proper social state

it could be any evil at all. Nor is there in this anti-Chinese feeling

anything essentially foreign. Those who talk about opposition to the Chinese

being anti-American shut their eyes to a great many facts if they mean

anything more than that it ought to be anti-American.

In short,

I am unable to see, in the conditions from which this agitation sprang,

anything really peculiar to California. I can not regard the anti-Chinese

sentiment as really peculiar, because it must soon arise in the East should

Chinese immigration continue; and because in connection in which we are

considering it, its nature and effects do not materially differ from those

which elsewhere are aroused by other causes. The main fact which underlies

all this agitation is popular discontent; and, where there is popular discontent,

if there is not one Jonah, another will be found. Thus, over and over again,

popular discontent has fixed upon the Jews, and among ourselves there is

a large class who make the “ignorant foreigner” the same sort of a scapegoat

for all political demoralization and corruption.

There has

been in California growing social and political discontent, but the main

causes of this do not materially differ from those which elsewhere exist.

Some of the factors of discontent may have attained greater development

in California than in older sections, but I am inclined to think this is

merely because in the newer States general tendencies are quicker seen.

For instance, the concentration of the whole railroad system in the hands

of one close corporation is remarkable in California, but there is clearly

a general tendency to such concentration, which is year by year steadily

uniting railroad management all over the country.

The “grand

culture” of machine-worked fields, which calls for large gangs of men at

certain seasons, setting them adrift when the crop is gathered, and which

is so largely instrumental in filling San Francisco every winter with unemployed

men, is certainly the form to which American agriculture generally tends,

and is developing in the new Northwest even more rapidly than in California.

Nor yet

am I sure that the characteristics of the press, to which San Franciscans

largely attribute this agitation, are not characteristics to which the

newspaper press generally tends. Certain it is that the development of

the newspaper is in a direction which makes it less and less the exponent

of ideas and advocate of principles, and more and more a machine for money-making.

There is,

however, a peculiar local factor which I am persuaded has not been without

importance. This is an intangible thing—a mere memory. But such intangible

things are often most potent. Just as the memory of previous revolutions

has disposed the discontented Parisian to think of barricades and the march

to the Hôtel de Ville, so has the memory of the Vigilance Committee

accustomed San Franciscans to think of extra-legal associations and methods

as the last but sovereign resort. These ideas have been current among a

different class from that which mans the Paris barricades.

The Vigilance

Committee of 1856, as most of the other California Vigilance Committees,

was organized and led by the mercantile class, and in that class its memories

have survived. The wild talk of the “sand-lot” about hanging official thieves

and renegade representatives, and the armed organizations of workingmen,

which have seemed at the East like the importations of foreign communism,

are in large measures but reflections and exaggerations of ideas current

in San Francisco counting-rooms and bank parlors. And it must be remembered,

in estimating the influence of this idea, that the Vigilance Committee

of 1856 was not merely successful in its immediate purposes, but gave birth

to a political organization that for many years thereafter managed the

local government and disposed of all its large prizes.

Yet, acting

with and running through this, has been, I think, a wider and more generally

diffused feeling—the disposition toward sharp repressive measures which

is aroused among the wealthy classes by symptoms of dissatisfaction and

aggression among the poor. That this feeling has of late years been growing

throughout the Union many indications show.

Be all this

as it may, the impulse that began these California agitations came from

the East. For the genesis of Kearneyism, or rather for the shock that set

in motion forces that social and political discontent had been generating,

we must look to Pittsburgh and to the great railroad strikes of 1877.

In California,

where a similar strike was about beginning—for the railroad company had

given notice of a like reduction in wages—these strikes excited an interest

that became intense when the telegraph told of the burning and fighting

in Pittsburgh. The railroad magnates, becoming alarmed, rescinded their

notice, but in the mean time a meeting to express sympathy with the Eastern

strikers had been called for the sand-lot in front of the new City Hall.

This meeting was called in response to a request of Eastern labor papers,

but happened to fall amid the excitement caused by the Pittsburgh riot.

The over-zealous authorities, catching, perhaps, the alarm that had induced

the railroad managers to rescind their reduction, arrested men who were

carrying placards advertising the meeting. In the excitement, wild reports

flew through the city that an incendiary meeting was to be held, and an

attempt made to burn the Pacific Mail Docks and Chinese quarter.

The meeting

was held, for the authorities soon saw that there was no reason for preventing

it. There was no talk of lawlessness or allusion to the Chinese on the

part of the promoters of the meeting or their speakers, but the excitement

showed itself by the raising, on the outskirts of the immense crowd, of

the cry, “To Chinatown!” a movement promptly stopped by the police; and

in remoter districts some Chinese wash-houses were raided by gangs of boys.

The papers—sensational to the last degree—made the most of this the next

morning, and in the excitement that the Eastern news had created, a meeting

was held in the rooms of the Chamber of Commerce, organized a Committee

of Public Safety, with the President of the Vigilance Committee of 1856

[William Tell Coleman] at its head, the hint being probably given by a

telegram that the citizens of Pittsburgh had restored order by organizing

a force armed with base-ball bats. In San Francisco the

pick-handle was

chose instead, and for some days a large number of men so armed perambulated

the streets. The meeting

was held, for the authorities soon saw that there was no reason for preventing

it. There was no talk of lawlessness or allusion to the Chinese on the

part of the promoters of the meeting or their speakers, but the excitement

showed itself by the raising, on the outskirts of the immense crowd, of

the cry, “To Chinatown!” a movement promptly stopped by the police; and

in remoter districts some Chinese wash-houses were raided by gangs of boys.

The papers—sensational to the last degree—made the most of this the next

morning, and in the excitement that the Eastern news had created, a meeting

was held in the rooms of the Chamber of Commerce, organized a Committee

of Public Safety, with the President of the Vigilance Committee of 1856

[William Tell Coleman] at its head, the hint being probably given by a

telegram that the citizens of Pittsburgh had restored order by organizing

a force armed with base-ball bats. In San Francisco the

pick-handle was

chose instead, and for some days a large number of men so armed perambulated

the streets.

Space will

not permit, nor is it necessary, to tell the story of this “battle of kegs.”

Ridiculous in some of its aspects, it was serious in others. There was

not the slightest necessity for this extra-legal organization and parade;

but, while San Francisco was represented to the world as a city on the

verge of riot and anarchy, a strong feeling of class irritation was engendered.

Among those

who carried a pick-handle in this “pick-handle brigade,” as it was christened,

was an Irish drayman, who has since become famous. [Denis] Kearney, a man

of strict temperance in all except speech, had built up a good business

in draying for mercantile houses, and accumulated, besides his horses and

drays, a comfortable little property. Up to this time he had taken no part

in politics, except to parade in torch light processions as a “Hayes Invincible,”

but for some two years had been a constant attendant at a sort of free

debating club, held on Sunday afternoons, and styled the Lyceum of

Self-Culture,

where he had gradually learned to speak in public, though the temperance

which he practiced and preached as to liquor and tobacco did not extend

to opinions or their expression. He was noticeable not merely for the bitter

vulgarity of his attacks upon all forms of religion, especially that in

which he had been reared, the Catholic, but for the venom with which he

abused the working classes, and took on every occasion what passed for

the capitalistic side.

With all

the vehemence with which he has since inveighed against “thieving capitalists”

and “lecherous bondholders,” he denounced the laziness and extravagance

of workingmen, declared that wages were far too high, and defended Chinese

immigration. Whether, with the suddenness not unnatural to such extremists,

Kearney really changed his opinions while carrying his pick-handle, the

change being hastened by some recent losses in stocks, or whether he merely

realized what political possibilities lay in the general feeling of discontent

and irritation, and how easily in times of excitement men may be organized,

makes little difference. He laid down his pick-handle, to put his drays

in charge of a brother, and go into politics.

His first

appearance in his new vocation attracted no attention. The Safety Committee

excitement passed immediately into the excitement of the impending legislative

and municipal election. Besides the regular parties, a number of independent

organizations or “side-shows” were in the field, many of them consisting

only of a high-sounding name and an Executive Committee, who found their

account in nominating candidates from the principal tickets and assessing

them for election expenses, candidates who were spending money heavily,

preferring to pay something to get on even the most insignificant ticket

rather than risk the loss of the few votes that might determine their election.

Amid all these “parties,” and “councils,” and “clubs,” the organization

of a “Workingmen’s Trade and Labor Union,” with one J.G. Day as president

and one D. Kearney as secretary, attracted no attention.

This new

organization, which besides a president and secretary, boasted also a treasurer,

stretched out a canvas bearing its name, and “resoluted” upon the necessity

of “patriotism and integrity in the public offices from the lowest to the

highest,” calling upon the laboring classes to unite “to elect candidates

in whom they could put their trust, and who are above suspicion.” This

being done, the new organization, by its president and secretary, proceeded

in the usual way to ascertain which of the principal candidates were most

above suspicion; but it printed no ticket, this particular movement to

secure “patriotism and integrity in the public offices” winding up on the

night before election in a row in which the treasurer and sergeant-at-arms

vainly endeavored to make the president and secretary “come to a divide”

on the amount collected, which they charged was between one and two thousand

dollars.

But the

master spirit of the ephemeral organization that thus unnoticed closed

its life of weeks was no ordinary “price club man,” who when one election

is over retires from politics until the next approaches. The knot of men

who had called the meeting of sympathy with the Eastern strikers had afterward

organized a workingman’s party and run a few candidates with a view to

the future, but their intentions were brought to naught by the more energetic

and audacious Kearney, who went to work without delay. On the Sunday after

the election he again attended, for the last time, the Lyceum of Self-Culture,

and, to the astonishment and amusement of the men whose ideas about the

rights and wrongs of the working classes he had been berating, told them

that they were a set of fools and blatherskites, and that he now proposed

to start in with the demand of “bread or blood,” and organize a party that

would amount to something.

The first

move was a meeting to consider the Chinese question, at which a speech

was made by a highly respected and prominent citizen; but when Kearney,

who officiated as secretary, got the stand, he dealt out some more highly

seasoned mental stimulant by reading a description of the burning of Moscow

as a suggestion of what might be in store for San Francisco. Then appropriating

the name of the Workingman’s party, Day and Kearney took to the sand-lot,

enlisting some other speakers. Though violent, these harangues would have

attracted little attention, and in fact the movement might have been choked

in infancy (for several rival factions started up, and opposition platforms

were erected within a few feet of each other), but for a powerful ally

of just the kind needed.

The two

San Francisco papers of largest circulation are the “Call” and “Chronicle,”

between whom intense rivalry has long existed. The “Call” has the greater

circulation and more profitable business, drawn largely from the working

classes. It is a good newspaper, but its editorial management is timorous

to a ridiculous degree. The “Chronicle,” whose principal proprietor [Charles

De Young] recently lost his life in a tragedy growing out of these occurrences,

is best described as a “live paper” of the most vigorous and unscrupulous

kind. As though a tacit partnership had been formed, Kearney began to call

upon workingmen to stop the “Call” and take the “Chronicle,” while the

“Chronicle” on its part advertised the meetings in the highest style of

the art, giving Kearney the greatest prominence and detailing its best

reporters to the manufacture and dress up his speeches. Thus advertised,

the meetings began to draw.

California

Street Hill is crowned by the palaces of the railroad nabobs—men who a

few years ago were selling coal-oil or retailing dry goods, but who now

count their wealth by the scores of millions. To complete the block which

one of these had selected for his palace, an undertaker’s homestead was

necessary. The undertaker wanted more than the nabob was willing to give,

and the latter cut short the negotiation by inclosing the undertaker’s

house on three sides with an immense board fence, probably the highest

on the Pacific coast, if not in the world. This veritable coffin, which

shuts out view and sun from the undertaker’s little home, and with the

common law, now abrogated in California by the code, would not have been

permitted, is one of the most striking features of the hill.

When, with

the assistance of the “Chronicle,” the meetings had begun to draw crowds,

largely composed of unemployed men, who after the harvest begin to collect

in San Francisco, and of a class that of late years has become numerous,

the professional beggars or strikers, a meeting was called for the top

of the California Street Hill, where the nabobs were regaled by the cheers

of a surging crowd, when it was proposed by one of the speakers—a pamphleteer

and newspaper writer well known in California for many years, but neither

before nor since took any part in the agitation—to celebrate Thanksgiving

by pulling down the big fence, if not removed by that time. This was too

much: the railroad magnates were frightened—even the “Chronicle” demanded

the arrest of the agitators; a sudden energy was infused into the authorities,

and they, with the proposer of the fence-destruction, were arrested on

charges of riot.

That these

arrests were ill advised the sequel proves. And it is to be remarked that

in all Kearney’s wild declamation there has been no direct incitement to

violence. He has talked about wading through blood, hanging official thieves,

burning the Chinese quarter, and generally “raising Cain,” but it has always

been with an “if.” He has never come any nearer to actually proposing any

of these things than Daniel O’Connell did to proposing armed resistance

to the English Government. Nor yet is it easy to point to anything which

Kearney has said that is really more violence or incendiary than things

said before with impunity. It was not [Denis] Kearney, but a republican

leader, a man of wealth, ability, and influence, who has held high position,

and was this year a prominent member of the National Republican Convention,

who first proposed that the Pacific Mail steamers should be burned at their

docks if they did not cease to bring Chinese; it was a bitter opponent

of Kearneyism who, amid thunders of applause, in the largest hall of the

city, first suggested that the Chinese quarter should be purified with

fire and planted with grass; while as to bitter denunciations of parties,

classes, and individuals, and prognostications of violence and calamity

if this, that, or the other was or was not done, there is probably nothing

that Kearney or his fellows have said that could not be matched from previous

political speeches or newspaper articles. That dangers may sometimes arise

from an abuse of the liberty of speech may be true, but it is so exceedingly

delicate a thing to attempt to draw any line short of the direct incitement

to specific illegal action, that the only course consistent with the genius

of our institutions is to leave such abuses to their own natural remedy.

It is only

where restrictions are imposed that mere words become dangerous to social

order, just as it only when gunpowder is confined that it becomes explosive.

Had the energy of the authorities been reserved for any lawless act, and

these agitators been left to agitate to their full content, except so far

as they might interfere with the free use of the thoroughfares, any momentary

interest or excitement would have soon died out, and the contempt which

follows swelling words without action would soon have left them powerless.

But the timidity which attaches to great wealth gained by questionable

means, and at once arrogant in its power and keenly sensitive of the jealousy

with which it is regarded, renders is possessors, surrounded as they must

be by sycophantic advisers, insensible to reason in moments of excitement.

“The thief doth fear each bush an officer.” And the man who from the windows

of a two-million-dollar mansion looks down upon his fellow citizens begging

for the chance to work for a dollar a day can not fail to have at times

some idea of the essential injustice of this state of things break though

his complacency, while murmurings of discontent assume vague shapes of

menace against which fear urges him to strike, though reason and prudence

would hold back a blow which can only irritate.

The dangers

to social order that arise from the glaring inequalities of wealth come

as much from this direction as from the discontent of the less fortunate

classes. It was this feeling that, organizing the “pick-handle brigade,”

prepared the way and gave the hint for agitation; it was this feeling that,

now striking blindly through the authorities, gave to an agitation dignity

and power.

More efficient

means to provoke a public sentiment in favor of the agitators could not

have been taken. Not only were the speakers arrest on charges which would

not bear legal authority, but new warrants were sworn out as quickly as

bail was offered. A pledge made by the agitators in prison, to hold no

more outdoor meetings and use no more incendiary language if the charges

against them were dismissed, was refused, and special counsel were employed

to prosecute. Outside the prison the same drunken spirit of arbitrary repression

showed itself, not only by driving crowds from the streets, but by breaking

up indoor meetings and installing captains of police as censors.

The reaction

was swift and strong, but it was not at first heeded. The charges against

the agitators were dismissed by the judge before whom they were brought,

but fresh charges were made, which were dismissed by juries. An ordinance

was rushed through the Board of Supervisors, under which it has never dared

to bring an action; a ridiculously oppressive law was hurried through the

Legislature, which was similarly a dead letter, and which at the next session

was repealed without a dissenting voice and hardly a dissenting vote.

These impotent

attempts at repression produced their natural result. The new party was

fairly started, brought into prominence and importance by the intemperance

which had sought to crush it.

The feeling

on the Chinese question has long been so strong in California as to give

certain victory to any party that could fully utilize it. But the difficulty

in the way of making political capital of this feeling has been to get

resistance, since all parties were willing to take the strongest anti-Chinese

ground. But the fear that the agitators had evidently inspired, the effort

to put them down, served as such resistance; and, though all parties were

anti-Chinese, the party they were endeavoring to start became at once the

anti-Chinese party in the eyes of those who were bitterest and strongly

in their feeling, while it at the same time became an expression, though

rudely and vaguely, of all sorts of discontent. It was evident that it

would be a political power for at least one election. The lower strata

of ward politicians were rushing into it as a good chance for office; the

“Chronicle,” which, at the first symptom of reaction, had redoubled its

service, placarded the State with resolutions of the new party asking workingmen

to stop the “Call.” That paper, losing heavily in subscribers, quietly

began to outdo the “Chronicle” in its reports and its puffery. Other papers,

recognized as organs of interests popularly regarded with dislike, did

their utmost by denunciation to keep Kearney in the foreground. Republican

politicians saw in the movement a division of the Democratic vote worth

fostering; Democratic politicians saw in it an element of future success,

on the right side of which the political wise men would keep; the municipal

authorities, remembering coming elections, passed from persecution to obsequiousness;

while the great railroad interest either came to a tacit understanding,

or had its agents install themselves in the new organization, using it

to help their friends and keep out their enemies, as they aim to use, and

generally succeed in using, all parties, and men of high social standing

did not hesitate, when it served their purpose, to furnish points and matter

for sand-lot harangues, or to speak at meetings which Kearney and his gang

had captured; for, until they met a very warm reception at a Democratic

meeting, they arrogated to themselves the right to interrupt and “bull-doze”

any meeting that did not suit them. (There have been no more meetings on

Nob Hill, or denunciation of the railroad magnates or great bonanza firm.

On the contrary, all the officials elected by the workingmen seem to have

been either employees or friends of the railroad, or people who could not

harm them, while a confidential attorney of large moneyed interests has

been the reputed confidential advisor of Kearney.)

Go to Part II of Kearney Agitation in California, by Henry George.

Return

to the top of the page.

|