|

||||

|

||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

THE WEST COAST 1942 Headquarters Western Defense

Command

Office of the Commanding General

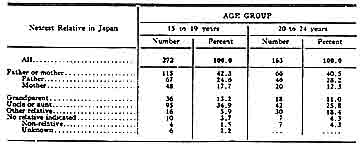

Action Under Alien Enemy Proclamations The ultimate decision to evacuate all person of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific Coast under Federal supervision was not made coincidentally with the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States. It was predicated upon a series of intermediate decisions, each of which formed a part of the progressive development of the final decision. At certain stages of this development, various semi-official views were advanced proposing action less embracing than that which finally followed. On December 7 and 8th, 1941, the President issued proclamations declaring all nationals and subjects of the nations with which we were at were to be enemy aliens. This followed the precedent of the last war, and was based upon the same statutory enactment which supported the proclamations of President Wilson in this regard. (See 50 U.S.C. 21.) By executive action, certain restrictive measures were applied against all enemy aliens on an equal basis. In continental United States, the Attorney General, through the Department of Justice, was charged with the enforcement and administration of these proclamations. Where necessary fully to implement his action, the Attorney General was assigned to responsibility of issuing administrative regulations. He was also give the authority to declare prohibited zones, to which enemy aliens were denied admittance or from which they were to be excluded in any case where the national security required. The possession of certain articles was declared by the proclamations to be unlawful, and these articles are described as contraband. Authority was granted for the internment of such enemy aliens as might be regarded by the Attorney General as dangerous to the national security if permitted to remain at large. In continental United States internment was left in any case to the discretion of the Attorney General. On the night of December 7th and the days that followed, certain enemy aliens were apprehended and held in detention pending the determination whether to intern. essentially, the apprehensions thus effected were based on lists of suspects previously compiled by the intelligence services, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and the Military Intelligence Service. During the initial stage of this action, some 2,000 persons were apprehended. Japanese aliens were included in their number. Beyond this, little was done forcefully to implement the Presidential proclamations. No steps were taken to provide for the collection of contraband and no prohibited zones were proclaimed. The Commanding General, during the closing weeks of December, requested that the War Department induce the Department of Justice to take vigorous action along the Pacific Coast. He sought steps looking toward the enforcement of the contraband prohibitions contained in the proclamations and toward the declaration of certain prohibited zones surrounding "vital installation" along the coast. The Commanding General had become convinced that the military security of the coast required these measures. His conclusion was in part based upon interception of unauthorized radio communications which had been identified as emanating from certain areas along the coast. Of further concern to him was the fact that for a period of several weeks following December 7th, substantially every ship leaving a West Coast port was attacked by an enemy submarine. This seemed conclusively to point to the existence of hostile ship-to-shore communication. The Commanding General requested the War Department to send a representative, and to arrange with the Department of Justice for an officer so that agency to meet with him at San Francisco, in order to consider the situation "on the ground." His objective was to crystallize a program of forthright action to deal with subversive segments of the population. Preliminary to this, and primarily at the request of the Commanding General, a number of discussions had been held between War and Justice Department representatives in Washington, D.C. The Provost Marshall, Major General Allen W. Gullion, the Assistant Secretary of War, Honorable John J. McCloy, the Chief of the Enemy Alien Control Unit, Department of Justice, Mr. Edward J. Ennis, and the Chief of the Aliens Division, Office of the Provost Marshal General, participated in these meetings. These conferences between War and Justice Department representatives in Washington were followed by the conference requested by the Commanding General in San Francisco. Mr. James Rowe, Jr., Assistant to the Attorney General, representative the Department of Justice. The Commanding General urged that the Justice Department provide for spot raids in various areas to determine the presence and possession of contraband; that it authorize the ready seizure of contraband than adopt means for collecting and storing it. He further requested that the Attorney General declare prohibited zones surrounding certain coastal installations. These conferences continued over the period between January 2nd and 5th, 1942, and, as an outgrowth of these meetings, the Department of Justice agreed to a program of enforcement substantially as desired by the Commanding General and Mr. Rowe (Appendix to Chapter II infra). The salient feature of the intended program was an agreement arranging for creation of prohibited zones. The Department of Justice agreed to declare prohibited zones of enemy aliens.; The extent and location of these zones was to be determined on the basis of recommendations submitted by the Commanding General. At the conclusion of these conferences, identical memoranda were exchanged on January 6, 1942 between the Commanding General and the Assistant Attorney General, Mr. James Rowe, Jr., crystallizing the intermediate understandings which had been developed. These were: "Following is a summary of the principles applicable and procedure to be followed in the implementation of the proclamations of the President dated December 7th and 8th, 1941, and the instructions and regulations of the Attorney General, respecting alien enemies in the Western Theater of Operations. These principles and procedure[s] were formulated in conferences during the past week between Lieutenant General J.L. DeWitt, Commanding General of the Western Theater of Operations, Mr. James Rowe, special representative of the Attorney General of the United States, Mr. N.J.L. Pieper, of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Major Karl R. Bendetsen, J.A.G.D., Office of the Provost Marshal General.After a series of surveys made by the Commanding Generals of the several Western Defense Command sectors, the Commanding General submitted a number of recommendations calling for the establishment of 99 prohibited zones in the State of California, and two restricted zones. These were to be followed by similar recommendations pertaining to Arizona, Oregon, and Washington. Primarily, the prohibited zones in California surrounded various points along the California Coast, installations in the San Francisco Bay area, particularly along the waterfront, and in Los Angeles and San Diego. The recommendation as to California was transmitted by the Commanding General by letter dated January 21, 1942, and was received from the Commanding General by the War Department on January 25, 1942, and was forwarded by the Secretary of War to the Attorney General on the same date. In a series of press releases the Attorney General designated as prohibited zones the 99 areas recommended by the Commanding General in California. Considerable evacuation thus was necessitated, but most of the enemy aliens concerned were able to take up residence in or near places adjacent to the prohibited zone. For example, a large prohibited zone followed the San Francisco waterfront area. Enemy aliens living in this section were required only to move elsewhere in San Francisco. Of course, only aliens of enemy nationality were affected, and no persons of Japanese ancestry born in the United States were required to move under the program. Although some problems were presented which required provision for individual assistance, essentially there was little of this involved. By arrangement with the Justice Department, the associated agencies of the Federal Security Agency were asked to lend assistance in unusually needy cases. Mr. Tom C. Clark, then the West Coast representative of the Anti-Trust Division of the Justice Department, supervised this phase of enemy alien control and coordinated all activities for the Justice Department. There was much conjecture that this was the forerunner of a general enemy alien evacuation. Mr. Clark and his Anti-Trust Division staff were deluged with inquiries and comments. Conflicting reports and rumors were rampant along the coast; public excitement in certain areas reached a high pitch, and much confusion characterized the picture. However, in essence, there was no substantial dislocation or disruption socially or economically of the affected groups. Need for Military Control and for Evacuation The Commanding General, meantime, prepared and submitted recommendations for the establishment of prohibited zones in Arizona, Oregon and Washington, similar to those he had prepared for California. Upon receipt of these supplemental recommendations, forwarded by the Secretary of War, the Attorney General declined to act until further study. In the case of Washington State, the recommended prohibited zone included virtually all of the territory lying west of the Cascades. A general enemy alien evacuation from this area would have been required. More than 9,500 persons would have been affected. No agency was then prepared to supervise or conduct a mass movement, and the Attorney General was not convinced of the necessity. As early as January 5, however, the Commanding General pointed to the need for careful advanced planning to provide against such economic and social dislocations as might ensure from any necessary mass evacuation. This was made eminently clear in a memorandum dated January 5, 1942, from the Commanding General to Mr. Rowe, during their initial conference at San Francisco. The point was also established that the Army had no wish to assume any aspects of civil control if there were any means by which the necessary security measures could be taken through normal civilian channels. In order to trace clearly the developments which ultimately lead to Executive Order No. 9066, and the establishment of military control, that memorandum is quoted in full at the end of this chapter. The Department of Justice had indicated informally that it did not consider itself in a position to direct any enforced migrations. The Commanding General's recommendations for prohibited zones in Washington and Oregon were therefore viewed with particular concern by the Department. No only did it feel that such action should be predicated on convincing evidence of the military necessity, it regarded the responsibility for collective evacuation as one not within its functions. The Attorney General, on February 9, 1942, formally advised the Secretary of War, by letter, that he could not accept the recommendation of the Commanding General for the establishment of a zone prohibited to enemy aliens in the States of Washington and Oregon of the extent required by him. It is already noted, however, that the Department of Justice had previously adopted such recommendations in California. He stated in part: "Your recommendation of prohibited areas for Oregon and Washington include the cities of Portland, Seattle and Tacoma and therefore contemplate a mass evacuation of many thousands * * *. No reasons were given for this mass evacuation* * * I understand that * * * Lieutenant General DeWITT has been requested to supply the War Department with further details and further material before any action is taken on these recommendations. I shall, therefore, await your further advise.The Commanding General therefore submitted a résumé of the military considerations which prompted his recommendation for a prohibited zone in Washington and Oregon embracing virtually the westerly half of those states. The Department of Justice, however, concluded that it was not in a position to undertake any mass evacuation, and declined in any event to administer such general civil control measures. Meanwhile, the uncertainties of the situation became further complicated. The enforcement of the contraband provisions was impeded by the fact that many Japanese aliens resided in premises owned by American-born person of Japanese ancestry. The Department of Justice had agreed to authorize its special field agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to undertake spot raids without warrant to determine the possession of arms, cameras and other contraband by Japanese, but only in those premises occupied exclusively by enemy aliens. The search of mixed occupancy premises or dwellings had not been authorized except by warrant only. (See Memo 1/5/42 at end of this chapter.) In the Monterey area in California a Federal Bureau of Investigation spot raid made about February 12, 1942, found more than 60,000 rounds of ammunition and many rifles, shotguns and maps of all kinds. These raids had not succeeded in arresting the continuance of illicit signaling. Most dwelling places were in the mixed occupancy class and could not be searched promptly upon receipt of reports. It became increasingly apparent that adequate security measures could not be taken unless the Federal Government placed itself in a position to deal with the whole problem. The Pacific Coast had become exposed to attack by enemy successes in the Pacific. The situation in the Pacific theatre had gravely deteriorated. There were hundreds of reports nightly of signal lights visible from the coast, and of intercepts of unidentified radio transmissions. Signaling was often observed at premises which could not be entered without a warrant because of mixed occupancy. The problem required immediate solution. It called for the application of measures not then in being. Further, the situation was fraught with danger to the Japanese population itself. The combination of spot raids revealing hidden caches of contraband, the attacks on coastwise shipping, the interception of illicit radio transmissions, the nightly observation of visual signal lamps from constantly changing locations, and the success of the enemy offensive in the Pacific, had so aroused the public along the West Coast against the Japanese that it was ready to take matters into its own hands. Press and periodical reports of the public attitudes along the West Coast from December 7, 1941, to the initiation of controlled evacuation clearly reflected the intensity of feeling. Numerous incidents of violence involving Japanese and others occurred; many more were reported but were subsequently either unverified or were found to be cumulative. To return again for a moment to the situation confronting the Commanding General. When the Attorney General advised that his Department was not in a position to declare as prohibited to enemy aliens the extensive areas recommended for such action in Oregon and Washington, he did not thereby establish the need for military control. It had become apparent that even those measures would not have satisfied the military necessities facing the Commanding General. For, by these means, no control would have been exerted over nearly two-thirds of the total Japanese population. Only about one-third were aliens, subject to enemy alien regulations. Because of the ties of race, the intense feeling of filial piety and the strong bonds of common tradition, culture and customs, this population presented a tightly-knit racial group. It included in excess of 115,000 persons deployed along the Pacific Coast. Whether by design or accident, virtually always their communities were adjacent to very vital shore installations, war plants, etc. While it is believed that some were loyal, it was known that many were not. It was impossible to establish the identity of the loyal and the disloyal with any degree of safety. It was not there was insufficient time in which to make such a determination; it was simply a matter of facing the realities that a positive determination could not be made, that an exact separation of the "sheep from the goats" was unfeasible. It could not be established, of course, that the location of thousands of Japanese adjacent to strategic points verified the existence of some vast conspiracy to which all of them were parties. Some of them doubtless resided there through mere coincidence. It seems equally beyond doubt, however, that the presence of others was not mere coincidence. It was difficult to explain the situation in Santa Barbara County, for example, by coincidence alone. Throughout the Santa Maria Valley in that County, including the cities of Santa Maria and Guadalupe, every utility, air field, bridge, telephone and power line or other facility of importance was flanked by Japanese. They even surrounded the oil fields in this area. Only a few miles south, however, in the Santa Ynez Valley, lay an area equally as productive agriculturally as the Santa Maria Valley and with lands equally available for purchase and lease, but without any strategic installations whatever. There were no Japanese in the Santa Ynez Valley. Similarly, along the coastal plain of Santa Barbara County from Gaviota south, the entire plain, though narrow, had been subject to intensive cultivation. Yet, the only Japanese in this area were located immediately adjacent to such widely separated points as the El Capitan Oil Field, Elwood Oil Field, Summerland Oil Field, Santa Barbara airport and Santa Barbara lighthouse and harbor entrance. There were no Japanese on the equally attractive lands between these points. In the north end of the county is a stretch of open beach ideally suited for landing purposes, extending for 15 or 20 miles, on which almost the only inhabitants are Japanese. Such a distribution of the Japanese population appeared to manifest something more than coincidence. In any case, it was certainly evident that the Japanese population of the Pacific Coast was, as a whole, ideally situated with reference to points of strategic importance, to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale should any considerable number of them have been inclined to do so. There were other very disturbing indications that the Commanding General could not ignore. He was forced to consider the character of the Japanese colony along the coast. While this is neither the place nor the time to record in detail significant pro-Japanese activities in the United States, it is pertinent to note some of them in passing. Research has established that there were over 124 separate Japanese organizations along the Pacific Coast engaged, in varying degrees, in common pro-Japanese purposes. This number does not include local branches of parent organizations, of which there were more than 310. Research and co-ordination of information had made possible the identification of more than 100 parent fascistic or militaristic organizations in Japan which have some relation, either direct or indirect, with Japanese organizations or individuals in the United States. Many of the former were parent organizations of subsidiary or branch organizations in the United States and in that capacity directed organizational and functional activities. There was definite information that the great majority of activities followed a line of control from the Japanese government, through key individuals or associations to the Japanese residents in the United States. That the Japanese associations, as organizations, aided the military campaigns of the Japanese Government is beyond doubt. The contributions of these associations toward the Japanese war effort had been freely published in Japanese newspapers throughout California. The extent to which Emperor worshipping ceremonies were attended could not have been overlooked. Many articles appearing in issues of Japanese language newspapers gave evidence that these ceremonies had been directed toward the stimulation of "burning patriotism" and "all-out support of the Japanese Asiatic Co-Prosperity Program. Numerous Emperor worshipping ceremonies had been held. Hundreds of Japanese attended these ceremonies, and it was an objective of the sponsoring organization to encourage one hundred per cent attendance. For example, on February 11, 1940, at 7:00 P.M., the Japanese Association of Sacramento sponsored an Emperor worshipping ceremony in commemoration of the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of Japan. Another group of Japanese met on January 1, 1941, at Lindsay, California. They honored the 2,601st Year of the Founding of the Japanese Empire and participated in the annual reverence to the Emperor, and bowed their heads toward Japan in order to indicate that they would be * * * ready to respond to the call of the mother country with one mind. Japan is fighting to carry out our program of Greater Asiatic co-prosperity. Our fellow Japanese countrymen must be of one spirit and should endeavor to united our Japanese societies in this country * * *.Evidence of the regular occurrence of Emperor worshiping ceremonies in almost every Japanese populated community in the United States had been discovered. A few example of the many Japanese associations extant along the Pacific Coast are described in the following passages: The Hokubei Butoku Kai. The Hokubei Butoku Kai or Military Virtue Society of North America was organized in 1931 with headquarters at Alvarado, Alameda County, California, and a branch office in Tokyo. One of the purposes of the organization was to instill the Japanese military code of Bushido among the Japanese throughout North America. This highly nationalistic and militaristic organization was formed primarily to teach Japanese boys "military virtues" through Kendo (fencing), Judo (Jiujitsu), and Sumo (wrestling).The manner in which this society became close integrated with many other Japanese organizations, both business and social, is well illustrated by the post address of some of these branches. The Heimusha Kai. The Heimusha Kai was organized for the sole purpose of furthering the Japanese war effort. The intelligence services (including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Military Intelligence Service and the Office of Naval Intelligence) has reached the conclusion that this organization was engaged in espionage. Its membership was composed of highly militaristic males eligible for compulsory military service in Japan. Its prime function was the collection of war funds for the Japanese army and navy. In more than 1,000 translated articles in which Heimusha Kai was mentioned, there was no evidence of any function save the collection of war relief funds. A prospectus was issued to all Japanese in the United States by the Sponsor Committee for Heimusha Kai in America. The prospectus is quoted as follows: "The world should realize that our military action in China is based upon the significant fact that we are forced to fight under realistic circumstances. As a matter of historical fact, whenever the Japanese government begins a military campaign, we, Japanese, must be united and everyone of us must do his part.The Heimusha Kai was organized on October 24, 1937, in San Francisco. The meeting took place at the Golden Gate Hall, and there were more than 200 members present. The following resolution was passed: "We, the members of the Japanese Reserve Army Corps in America are resolved to do our best in support of the Japanese campaign in China and to set up an Army Relief Department For Our Mother Country."According to reliable sources there were more than 10,000 members of the Heimusha Kai in 1940... . One extremely important obstacle in the path of Americanization of the second-generation Japanese was the widespread formation, and increasing importance, of the Japanese language schools in the United States. The purposes and functions of these Japanese language schools are well known. They employed only those text books which had been edited by the Department of Education of the Japanese Imperial Government. In order to assist the Japanization of the second generation, the Zaibei Ikuei Kai (Society for the Education of the Second Generation in America) was organized in Los Angeles in April 1940. "With the grace of the Emperor, the ZAIBEI IKUEI KAI is being organized in commemoration of the 2,600th Anniversary of the Founding of the Japanese Empire to Japanize the second and third generations in this country for the accomplishment of establishing a greater Asia in the future * * *. In California alone there were over 248 schools with an aggregate faculty of 454 and a student body of 17,800. The number of American-born Japanese who had been sent to Japan for education and who were now in the United States could not be overlooked. For more than twenty-five years American-born progeny of alien Japanese had been sent to Japan by their parents for education and indoctrination. There they remained for extended periods, following which they ordinarily returned to the United States. The extent of their influence upon other Nisei Japanese could not be accurately calculated. But it could not be disregarded. The Kibei Shimin movement was sponsored by the Japanese Association of America. Its objective for many years had been to encourage the return to America from Japan of American-born Japanese. When the movement started it was ascertained that there were about 50,000 American-born Japanese in Japan. The Japanese Association of America sent representatives to Japan to confer with Prefectural officials on the problems of financing and transportation. The Association also arranged with steamship companies for special rates for groups of ten or more so returning, and requested all Japanese associations to secure employment for returning American-born Japanese. During 1941 alone more than 1,573 American-born Japanese entered West Coast ports from Japan. Over 1,147 Issei, or alien Japanese, re-entered the United States from Japan during that year. The 557 male Japanese less than twenty-five years of age who entered West Coast ports from Japan during 1941 had an average age of 18.2 years and had spent an average of 5.2 years in Japan. Of these, 239 had spent more than three years there. This latter group had spent an average of 10.2 years in Japan. Of the 239 males who spent three years or more abroad, 180 were in the age group 15 to 19 (with an assumed average age of 17.5 years) and had spent 10.7years abroad. In other words, these 180 Kibei lived, on an average, 6.8 years at the beginning of their life in the United States and the next 10.7 years in Japan. Forty of the 239 who had spent three or more years abroad were in the age group 20 to 24, with an assumed average age 22.5. These were returning to the United States after having lived here, on the average, for their first 13 years and having spent the last 9.5 years in Japan, including one or more years when they were of compulsory (Japanese) military age. The table below indicates the nearest relative in Japan for the age groups 15 to 19, and 20 to 24 years of age. It will be noted that 42.3 per cent of those in the 15 to 19 year group lived with a father or mother in Japan, and that 13.2 lived with a grandparent. In other words, more than 50 per cent of this group of Kibei had a parent or grandparent in Japan, and it is reasonable to assume that in most instances these Kibei lived with this nearest relative.  Combining this information with that from the preceding table, it is seen that in a group of an average age of 17.5 years who were returning to the United States after having spent an average of 7.4 years aboard continuously (in other words, from the time they were ten years of age) one-half had lived with their parent or grandparent in Japan. Yet, this group consists entirely of American citizens and almost entirely of men who are of draft age at the present time! Of the Kibei in Hawaii, Andrew W. Lind, Professor of Sociology, University of Hawaii, says: "Finally, there is the rather large Kibei group of the second generation who, although citizens of the United States by virtue of birth within the Territory [of Hawaii], are frequently more fanatically Japanese in their disposition than their own parents. Many of these individuals have returned from Japan so recently as to be unable to speak the English language and some are unquestionably disappointed by the lack of appreciation manifested for their Japanese education." (American Council Paper No. 5, page 187, American Council, Institute of Pacific Relations, 129 East 52nd Street, New York.) It was, perforce, a combination of factors and circumstances with which the Commanding General had to deal. Here was a relatively homogeneous, unassimilated element bearing a close relationship through ties of race, religion, language, custom, and indoctrination to the enemy. The mission of the Commanding General was to defend the West Coast from enemy attack, both from within and without. The Japanese were concentrated along the coastal strip. The nature of this area and its relation to the national war effort had to be carefully considered. The areas ultimately evacuated

of all persons of Japanese ancestry embraced the coastal area of the Pacific

slope. In the States of Washington and Oregon to the north, Military Area

No. 2 contains all that portion lying westerly of the eastern bases of

the Cascade Mountains. In other words, the coastal plain, the forests,

and the mountain barrier. In California the evacuation program encompassed

the entire State-that is to say, not only Military Area No. 1 but also

Military Area No. 2. Military Area No. 2 in California was evacuated because

(1) geographically and strategically the eastern boundary of the State

of California approximates the easterly limit of Military Area No. 1 in

Washington and Oregon (figure 1 shows the boundaries of these two Military

Areas), and because (2) the natural forests and mountain barriers, from

which it was determined to exclude all Japanese, lie in Military Area No.

2 in California, although these lie in Military Area No. 1 of Washington

and Oregon. A brief reference to the relationship of the coastal states

to the national war effort is here pertinent.

That part of the States of Washington, Oregon, and California which lies west of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Ranges, is dominated by many waterways, forests, and vital industrial installations. Throughout the Puget Sound area there are many military and naval establishments as well as shipyards, airplane factories and other industries essential to total war. In the vicinity of Whidby Island, Island County, Washington, at the north end of the island, is the important Deception Pass bridge. This bridge provides the only means of transit by land from important naval installations, facilities, and properties in the vicinity of Whidby Island. This island afforded an ideal rendezvous from which enemy agents might communicate with enemy submarines in the Strait of Juan de Fuca or with other agents on the Olympic Peninsula. From Whidby and Camano Islands, comprising Island County, the passages through Admiralty Inlet, Skagit Bay, and Saratoga Passage from Juan de Fuca Strait to the vital areas of the Bremerton Navy Yard and Bainbridge Island can be watched. The important city of Seattle with its airplane plants, airports, waterfront facilities, Army and Navy transport establishments, and supply terminals required that an unassimilated group of doubtful loyalty be removed a safe distance from these critical areas. . . . [There is] a high concentration of persons of Japanese ancestry in the Puget Sound area. Seattle is the principal port in the Northwest; it is the port from which troops in Alaska are supplied; its inland water route to Alaska passes the north coast of Washington into the Straits of Georgia on its way to Alaska. The lumber industry is of vital importance to the war effort. The State of Washington, with Oregon and California close seconds, produces the bulk of sawed lumber in the United States. The large area devoted to this industry afforded saboteurs unlimited freedom of action. The danger from forest fires involved not only the destruction of valuable timber but also threatened cities, towns, and other installations in the affected area. The entire coastal strip from Cape Flattery south to Lower California is particularly important from a protective viewpoint. There are numerous naval installations with such facilities constantly under augmentation. The coastline is particularly vulnerable. Distances between inhabited areas are great and enemy activities might be carried on without interference. The petroleum industry of California and its great centers of production for aircraft and shipbuilding, are a vital part of the lifeblood of a nation at war. The crippling of any part of this would seriously impede the war effort. Through the ports of Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, flow the sinews of war-the men, equipment, and supplies for carrying the battle against the enemy in the Pacific... .[A] high concentration of this segment of the population surround nearly all these key installations. In his estimate of the situation, then, the Commanding General found a tightly knit, unassimilated racial group, substantial numbers of whom were engaged in pro-Japanese activities. He found them concentrated in great numbers along the Pacific Coast, an area of the utmost importance to the national war effort. These considerations were weighed against the progress of the Emperor's Imperial Japanese forces in the Pacific. This chapter would be incomplete without a brief reference to the gravity of the external situation obtaining in the Pacific theater. It is necessary only to state the chronology of war in the Pacific to show this. At 8:05 A.M., the 7th of December, the Japanese attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor without warning. Simultaneously they struck against Malaysia, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and Wake and Midway Islands. On the day following, the Japanese Army invaded Thailand. Two days later the British battleships H.M.S. Wales and H.M.S. Repulse were sunk off the Malay Peninsula. The enemy's successes continued without interruption. On the 13th of December, Guam was captured and on successive days the Japanese captured Wake Island and occupied Hong Kong, December 24th and 25th, respectively. On January 2nd Manila fell and on the 27th of February the battle of the Java Sea resulted in a crushing naval defeat to the United Nations. Thirteen United Nations' warships were sunk and one damaged. Japanese losses were limited to two warships sunk and five damaged. On the 9th of March the Japanese Imperial forces established full control of the Netherlands East Indies; Rangoon and Burma were occupied. Continuing during the course of evacuation, on the 9th of April, Bataan was occupied by the Japanese and on May 6th Corregidor surrendered. On June 3rd, Dutch Harbor, Alaska, was attacked by Japanese carrier based aircraft and, with the occupation by the Japanese on June 7th of Attu and Kiska Islands, United States territory in continental Northern America had been invaded. As already stated, there were many evidences of the successful communication of information to the enemy, information regarding positive knowledge on his part of our installations. The most striking illustrations of this are found in three of the several incidents of enemy attacks on West Coast points. On February 23, 1942, a hostile submarine shelled Goleta, near Santa Barbara, California, in an attempt to destroy vital oil installations there. On the preceding day the shore battery in position at this point had been withdrawn to be replaced by another. On the succeeding day, when the shelling occurred, it was the only point along the coast where an enemy submarine could have successfully surfaced and fired on a vital installation without coming within the range of coast defense guns. In the vicinity of Brookings (Mt. Emily), Oregon, an enemy submarine based plane dropped incendiary bombs in an effort to start forest fires. At that time it was the only section of the Pacific Coast which could have been approached by enemy aircraft without interception by aircraft warning devices. Similarly, a precise knowledge of the range of coast defense guns at Astoria, Oregon, was in the possession of the enemy. A hostile submarine surfaced and shelled shore batteries there from the only position at which a surfaced submarine could have approached the coastline close enough to shell a part of its coast defenses without being within range of the coastal batteries. In summary, the Commanding General was confronted with the Pearl Harbor experience, which involved a positive enemy knowledge of our patrols, our naval dispositions, etc., on the morning of December 7th; with the fact that ships leaving West Coast ports were being intercepted regularly by enemy submarines; and with the fact that an enemy element was in a position to do great damage and substantially to aid the enemy nation. Time was of the essence. The Commanding General, charged as he was with the mission of providing for the defense of the West Coast, had to take into account these and other military considerations. He had no alternative but to conclude that the Japanese constituted a potentially dangerous element from the viewpoint of military security–that military necessity required their immediate evacuation to the interior. The impelling military necessity had become such that any measures other than those pursued along the Pacific Coast might have been "too little and too late." IN: Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942, Headquarters Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Office of the Commanding General, Presidio of San Francisco, California; Chapters 1 and 2. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1943. Return to the Japanese Internment Page Go to Appendix to Chapter II |