TROOPS WITH MACHINE GUNS GUARD CARGO MOVEMENTS Few Pickets Venture on Embarcadero Where Bloody Riots Started; Man shot in East Bay Attack.

Martial law reigned on the waterfront today. Under muzzles of machine

guns manned by the National Guard, the Industrial Association and the Belt

Line Railway resumed the movement of cargo from

strike- The laws of war automatically went into effect when the militia took possession of the Embarcadero in the wake of Gov. Frank Merriam's proclamation of tumults and riots in the city, Atty. Gen. U.S. Webb rules. The entire city may be put under martial law, if strike disturbances intensify, the attorney general declared. So efficient was the protection afforded by guardsmen that the Industrial Association opened a second warehouse for the storage of goods moved from Pier 38. An odd, and perhaps ominous change in the strikers' tactics became increasingly evidence on the scene of yesterday's battles. Quiet prevailed and squadrons of strikers themselves were moving among groups of men ordering them to disperse. "General strike!" was whispered. Strikers, held in check by police and troops, were hoping to be able to wield their last and perhaps most effective weapon to enforce their demands.

Though all was quiet here, the East Bay reported the first strike casualty of the day. Clayton Minor, 27, an Oakland striker, was shot in the stomach and critically wounded when he and four others attacked a San Francisco dock worker in Alameda. Toll of yesterday's bloody rioting here stood at two dead from revolver fire. 30 wounded by bullets and 43 others clubbed, gassed and stoned. With the armed forces in complete control of the waterfront, the possibility that the Atlantic coast might be paralyzed by a sympathy strike of longshoremen increased.

Protected by police and the militia, land crews of the San

Francisco-

Hoodlums last night hurled rocks through three plate- A telephoned threat that the National Adhesives Co. building, 883 Bryant st., would be blown up some time today was received at the company's offices, J.D. Light, manager, reported to police, according to the Industrial Association. He attributed the threat to the company's receipt of some merchandise from the docks, the association said.

A caravan of 34 trucks laden with perishables for San Francisco was halted at Tracy by two asserted San Francisco strikers. Drivers were warned not to continue or their lives and homes would be endangered. Eighteen of the trucks halted. The balance continued to San Francisco. Eight asserted pickets and several reputed Communists were run out of Tracy by police, after the threats were made. Sheriff M.J. Driver, Alameda county, sent two radio cars to clear highways of strike pickets when Charles Reuter, Oakland commission merchant, complained a truckload of oranges consigned to him from Los Angeles had been halted in Altamont pass and the driver threatened.

Other strike- Promising to maintain "a solid I.L.A. Union" and return to work at once under the June 16 agreement, Lee J. Holman, deposed president of the I.L.A., applied to Mr. Ryan today for a new charter in the name of the "San Francisco Bay District Longshoremen's Association." E. Raymond Cato, chief of the State Highway Patrol, issued orders from Los Angeles to double the number of officers on the road in the affected area, if necessary, to insure safe highway movements. Explaining his ruling on martial law, Atty. Gen. Webb said: "Military government is a state governor's resource, and therefore supreme. "In accordance with the governor's proclamation, the commander of the National Guard may move across the present bounds of the disturbance whenever he or the governor sees fit. "Under military law a court martial may be set up as a substitute to civil tribunals. Speedy trials may be dispatched in such a tribunal. Parties would have the right to file writs of habeas corpus but to obtain them under military rules would be another thing."

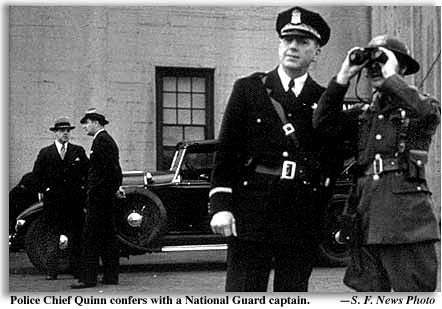

"There will be no duplication of effort," said Police Chief Quinn. "The National Guard will patrol the waterfront, and no farther. We will guard other areas where there has been trouble, such as Rincon Hill, the Third and Townsend district and Mission, Howard and Steuart sts." Chief Quinn also ordered his men to round up all Communists engaged in distributing subversive literature. And Gov. Merriam, in calling out the militia, had said that while his proclamation actually embraced the entire city, the National Guard would continue themselves to protecting state property along the Embarcadero. However, when the first truck left Pier 38, a squad of soldiers was patrolling Third sts between King and Berry sts., a machine gun was set up near a pile of bricks which furnished rioters with ammunition Tuesday, another machine gun was posted at King and the Embarcadero and three more machine guns were on the second floor ramp of the state terminal which runs from the Embarcadero to Third and Berry sts. These guns had a full range of the warehouse and adjoining streets.

Machine guns were also located in front of the Matson docks, each manned by a crew of four. On the roofs of Piers 34, 36 and 40 were expert riflemen, posted to keep a watch for snipers. The consensus among National Guard officers was that for the present the Guard will devote itself to protection of state property. This includes Third and Townsend sts., because the Belt Line tracks run there. Troops on the waterfront were augmented by 390 additional guardsmen, including 250 men of the 184th Infantry from Santa Rosa, Petaluma and Napa and 140 men of the same regiment from San Jose. These additions brought the total militia command on duty here to nearly 2400.

Maj.- Asked what the guard would do if strikers hurled rocks at the troops across the Embarcadero deadline, both men smiled and replied: "We're here to preserve order. Our men, however, will not stand for injury of any kind, even verbal."

Lieut. Col. C.D. O'Sullivan, guard intelligence officer said:

"Our jurisdiction is not limited but at present we are working in close

co- A report was current among strikers that Harry Bridges, chairman of the joint marine strike committee, tried vainly to get orders to strikers to retreat and offer no violence after the first shootings occurred at First and Harrison sts. yesterday. The reports said that so great was the confusion he could not get the order spread, and the riots wept to even more disastrous lengths. Mr. Bridges could not be reached for comment. Movement of trucks from Pier 38 was going forward without interruption, for in addition to the guardsmen in front of the pier and along the route, a number of policemen were on duty. The trucks were carrying furniture, piece goods and iron pipe and officers said the movement would keep up until the pier was cleared of all goods consigned to San Francisco merchants. The new warehouse was a 139 Townsend st. The first trucks to move goods into it were two laden with sheet metal that started from Pier 38 at 10:40 a.m. with a heavy police motorcycle escort, and police lining both sides of Townsend st. from the Embarcadero to the warehouse. The trip was uneventful. Managing Director A.E. Boynton of the Industrial Association announced that as soon as Pier 38 is cleared movement of cargoes from other piers will start "unless normal hauling is under way by that time," but he declined to divulge which would be the next pier undertaken or whether new warehouses will be opened.

Col. Mittelsteadt said that "while this is new to us we have assured Chief

Quinn 100 per cent co- "We mean business," the colonel added. "We now have a total of 2000 men on duty on the waterfront and should circumstances necessitate additional men, we have sufficient men in Oakland to bring over here at a moment's notice."

Col. O'Sullivan spiked rumors that southern California Guardsmen might be brought here by saying that they would go into their summer encampment at San Luis Obispo Sunday on schedule. Every pier along the entire Embarcadero had is quota of guardsmen this morning, about 15 men to a pier. Inside the dock houses were their cots, mounted machine guns and a consignment of the dread vomit gas. Outside, 10 men stood ready for duty. Five others were on sentry [duty], maintaining contact with sentries on adjoining piers. The guardsmen meant business. They had orders, they said, to challenge everyone at 50 feet, to shoot if the challenged one failed to halt. Persons with credentials were able to be allowed to pass, all others were to be ordered off the waterfront. Injured guardsmen will be given first aid at Central Emergency Hospital and then taken to St. Luke's Hospital, Dr. J.C. Geiger, city health director, announced. The report that the joint maritime strike committee had ordered a virtual suspension in picketing was denied by R.B. Mallen, publicity chairman. Mr. Mallen also denied the I.L.A. had issued any new orders against violence by pickets.

"That has been a standing order since the beginning of the strike," he said.

"We are, however, re-

President Roosevelt's National Longshoremen's Board, still seeking a settlement formula, met to open an answer from the Waterfront Employers' Union to their plea that the employers voluntarily ask arbitration. Refusal would mean the start of public hearings by the board. Incidents were few and far between on the waterfront. An empty boxcar was damaged by fire at the Belt Line's Kearny and Bay sts. yards. Firemen said the fire apparently had been started by a phosphorus cake "planted" in the car. A truck loaded with sheep from Fortuna caught fire on the Embarcadero opposite Pier 32. Guardsmen and police helped C.L. Hatch, the driver, extinguish the blaze. Telephone threats that if St. Luke's Hospital continued to treat strikebreakers it would be boycotted by all union labor were received by Mrs. Catherine Askew, telephone operator. Police were investigating.

The Alameda shooting occurred when Chester I. Hibbard, 41, Matson line dock electrician, 3262 Thompson st., Alameda, was attacked. Repeatedly warned to stay away from the docks, Hibbard said he had armed himself and when the five men attacked him he drew his weapon. In a struggle with Minor for the gun the striker was shot. Hibbard immediately surrendered to Alameda police, who were awaiting word from Dist. Atty. Earl Warren as to what charge to place against him. Minor was feared near death in Alameda County Emergency Hospital. Eastern sympathy strike talk grew when it was learned the executive board of the International Longshoremen's Association had been summoned into a special session. Joseph P. Ryan, international president, said he had called the meeting "to see what support we shall give the west coast strike." He refused to say whether a general strike was contemplated.

The National Guard took over the waterfront with perfect military precision. A campfire glowed beside the railroad tracks, flashing its light on steel bayonets.

Neat little, deadly little machine guns peeked out over the sides of

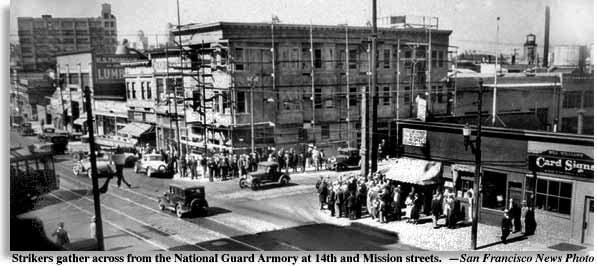

bullet- War! It was war for those picketing longshoremen who sat about the fire near the Belt Line Railroad and watched the California National Guard move onto the waterfront. It was war for those grim faced, nervous boys who had been called to strike duty from their schools, office work and play to protect life and property in San Francisco. It was war, too, for veterans of other campaigns, men who had gone through the World War and had seen action many times. Late at night they moved onto the waterfront and took their posts. There they will eat and sleep for "duration." It was war as the call was flashed out over specially installed telephones from the State Armory at 14th and Mission sts. to the men of the 250th Coast Artillery to report for duty.

All during the afternoon they gathered, were issued equipment, full packs

with blankets, mess kits—

Supplementing his order was this from Capt. Bedford W. Boyes, plans and training officer in charge of placing the guard units: "We want strikers to realize that we are soldiers and not policemen. We do not intend to engage in hand-to-hand combat. We are not going to hit anyone on the head with clubs because we are not equipped with them." Neither will the guard use gas, he declared, police experience having proved gas an unreliable weapon due to strong wins that sweep the waterfront. He admitted, however, that troopers were equipped with nauseating and tear gas. On the other hand, a marked lack of gas masks to protect the guard from the fumes was noticed at the Armory as equipment was being issued. Officers were reluctant to comment, but it was learned that sufficient masks were not available.

As they prepared to go into action, several officers called their homes and told their families to go elsewhere to sleep until the difficulty is over. "We have all received threats," one captain said. "The strikers have been watching our houses for weeks and have taken the numbers of our automobiles."

Silent sentries walked back and forth, back and forth, with fixed bayonets. None was allowed close to the Armory unless he had credentials. Finally, silent figures, bulky and slumped under the heavy packs, marched from the rear of the building to Julian st. They gathered in little clusters, awaiting orders to climb aboard the trucks. A cigaret glowed.

"Put out that cigaret," came a grimly humorous shout out of the

night— Then came the trucks, squat, efficient things. They had been stored in the basement of the Armory and were lifted to the street level by a hydraulic elevator.

As the first one nosed out onto 14th st. it stalled. A cheer went up from the

crowd. A second cheer greeted renewed throbbing of the

motor—

Down 14th to Valencia sts., down Valencia to Market, out Van Ness to

Lombard and down Lombard to the waterfront went the first fleet of 14

trucks— First the motorcade stopped at Pier 35 and then deployed along the north side of the Ferry Building. The 250th is to have charge of that side, with the 159th Infantry, recruited from other bay districts, in control along the south side. A post command previously had been set up at the Ferry Building. Delay in starting to the waterfront was attributed to slowness of lunch boxes to arrive at the Armory. Many of the boys flopped on the floor, against gun carriages or on their bed rolls and went to sleep in the chill air. It was war! In their sector, the national guardsmen are in supreme command, with the power to make arrests and either set up military courts or turn their prisoners over to civil authorities. They made their first arrest last night when Maj. Reed Clark seized Edgar Brooks, 1284 Page st., after he had refused to move on. He was turned over to police. With 2000 men already on the waterfront, Adj. Gen. Seth Howard issued "warning orders" to another thousand troops in outlying districts to be ready for call. And in the background hung the remote possibility of the regular army being called if any government property is threatened. It was pointed out that the Ferry Postoffice constitutes federal terrain and the army would have the right to patrol within a mile radius of that point. Commanding the National Guard of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and part of Oregon is Dr. David P. Barrows, Berkeley educator and veteran of the World War and the Kolchak campaign in Siberia. Adjt. Gen. Howard, commander of the California area, is expected to take personal command, with headquarters in Oakland.

The East Bay was quiet. There were no guardsmen on the waterfront, but patrols were posted around armories in Oakland and Berkeley. The local armory at 14th and Mission sts. was also closely guarded as a result of reports that strikers had threatened to blow it up. A wartime censorship was clamped down on the Embarcadero. G.H.Q. at the Ferry Building held press conferences but gave out little information in between them. Orderlies were trotting in, saluting, clicking heels. Orders were barked, officers were studying maps.

Col. Middelstaedt made it clear that wartime conditions existed, that his men are equipped with rifles, bayonets and machine guns and that the Embarcadero will not be a safe place "for persons whose reasons for being there are not sufficient to run the risk of serious injury." Chief Quinn echoed that sentiment when he made a new appeal to citizens to keep away from the waterfront.

But a good many policemen, from the chief down, resented the presence of

the citizen- "We have the situation in hand and I'm afraid the National Guard coming in will result in much bloodshed and many deaths," said Chief Quinn. "In a situation like this, the National Guard sets a deadline and then shoots anyone who crosses it. The strikers don't understand these kind of orders and are quite likely to barge across deadlines. "And rifles are being put in the hands of inexperienced men." "Then we'll have to deal with the strikers, and the mere presence of those soldiers on the waterfront may make it all the tougher for us."

Chief Quinn and little, dynamic Theodore Roche, president of the Police

Commission, were in active command during the peak of yesterday's

rioting. Both escaped injury by inches when strikers hurled bricks at their

cars. Both planned to be in the center of things again today, if any trouble

developed.

Return to the Museum's General Strike Page.

|

The question of how far guard patrols would extend bobbed up with the

movement of trucks from Pier 38.

The question of how far guard patrols would extend bobbed up with the

movement of trucks from Pier 38.