OF CIVIL WAR: 2 DEAD, MANY HURT Police Cover Wide Area in Coping With Bitterest Industrial San Francisco awoke today with a bad taste in its mouth—

Bloodshed— Among the no-man's-land of the Embarcadero and the far-flung area from Market st. to Rincon Hill, on up to Second st., the battles raged.

Yesterday's ware of the streets had for its Bunker Hill the battle of Rincon

Hill—

Police revolvers cracked into mobs of howling, cursing strikers. Tear gas guns and hand grenades exploded their blinding fumes. Riot sticks cracked upon scores of heads.

And from the embattled strikers—driven from one sector to still other

battle grounds— "The troops are called out!" As the press flashed this word, husky voices relayed it on to charging police, to the driven masses of strikers. By 1 p.m. Gov. Merriam, who kept informed of the riots one after the other, ordered mobilization of National Guardsmen. At 3:03 o'clock he issued the proclamation to send them with bayoneted rifles, machine guns and nauseating gas onto the Embarcadero. The bitter rioting went on.

Twice yesterday strikers' attacks centered on the movement of Belt Line trains to the piers. The opening clash came at 8 a.m. More than 2000 pickets looked on and growled as a locomotive moved two cars at the Matson docks, Piers 30 and 32.

Police decided to clear the Embarcadero. The crowd fought back with

hurtling rocks. Milling strikers surrounded the box cars. Smoke began

curling up from the cars. Fire apparatus arrived— The battle of Rincon Hill became the major engagement of the morning. The picket forces were divided. There were the hundreds as near the Embarcadero as they could get. Some 2000 other men had taken Rincon Hill. Out of Pier 38 came the motor trucks of the Industrial Association, the port openers.

From their Rincon Hill vantage point, pickets could see their forces being

beaten back from the Belt Line tracks and watch another

gas-

A gang of 500 men ran down the Harrison st. bridge toward the melee

below. Their war whoop was blood curdling. They let fly stones at

bluecoats. Shots cracked out—

Grass Fires Add to Confusion Then grass fires broke out on Rincon Hill. The tear gas squad checked the strikers' foray with a barrage of fumes that spread up and up on Rincon Hill. Clouds of gas and grass smoke! To the din of cursing men were added the screams of fire engine sirens. Rioters fought back the firemen. The hoses were turned on the strikers who were knocked rolling in the mud. Then came the police mopup. Search was made of Rincon Hill houses for possible snipers. Everyone was driven off the hill, the pickets falling back sullenly before police revolvers and clubs.

Again another attack on the trains was staged. After a lunch-

Came then the Ferry Building outbreaks, the Seaboard Hotel affray and bloodies, most dramatic battle of the day near Steuart and Mission sts., as the police attempted to clear the whole waterfront area. Midst a barrage of rocks that endangered several onlookers pressed against the Ferry Building, police cleared the nearby region. Again, though, a fight broke out at the south end of the vehicular tunnel in front of the Ferry Building. One officer, his face slashed, aimed a revolver at the crowd. A fellow officer knocked his gun up. Then both officers hurled gas grenades. Police chased the strikers up Market st. The barrage of tear gas temporarily isolated the Ferry Building. The war moved into the stage of heavy shooting.

With the strategy of warfare, a milling mass of strikers hemmed in a few officers in front of I.L.A. headquarters, 113 Steuart st. One officer emptied a riot gun and pistol into the crowd. H.P. Sperry, a striker, fell with a shot in his back. He died in the hospital. Another striker was perhaps fatally wounded. Along Steuart st. from Market to Howard the battle flared. More shots were fire, more tear gas. A woman and two other passengers were shot in street cars. Two more strikers were reported to have been carried into the Steuart st. headquarters of the striking longshoremen. Police hurled tear gas bombs into the headquarters. Wounded were dragged inside. A husky striker lay wounded at Steuart and Mission. Police Chief Quinn road up, proffered the patrol wagon as an ambulance for him. "Go to hell," spat the wounded man. "I won't ride in that damn thing." In a nearby lot a man emptied a revolver at police, escaped unwounded, as two officers returned the fire. The mopping out of the Embarcadero of strikers required onslaughts by helmeted officers into the runway of the Y.M.C.A. Hotel, precipitated a tempestuous stand at the Seaboard Hotel, Howard st. and the Embarcadero.

A tear bomb was sent shattering through the hotel window, more were

hurled, spreading dense fumes about the entrance and into the lobby. Men

entrapped inside by the gas shouted for help. Police wearing masks raised a

ladder against a fire escape and carried bullet- Back along the streets and sidewalks where San Francisco's worst strike war had broken were pools of blood. In the hospitals were men feared dying and others injured. Gov. Merriam in Sacramento meantime was directing Adj. Gen. Seth F. Howard to have the guard in readiness.

He learned with anger that all work in San Francisco on the

San Francisco-

The killings roused the governor to declaration of the state's official entry

into the war. Declaring "there exists in San Francisco a state of tumult, riot

and other emergencies ...

By night 2000 guardsmen were dispatched to the waterfront. Mayor Rossi, too, had refused to ask for troops. He was having a verbal battle, though, with strike leaders, headed by Harry Bridges, chairman of the joint marine strike committee, who marched into his office and heatedly charged wanton police violence. One protesting leader was ejected from the office in the hot exchange of words. "The police are going to protect life and property," declared the mayor. "Why don't you arbitrate? You could have your jobs back today, if you would." The strike committee also wired the White House in protest against the police warfare.

Struggling on for a peaceful settlement, the President's National

Longshoremen's Board during the day sought to obtain arbitration. The

board conferred with ship owners' spokesmen, pleaded that employers

agree to arbitrate their differences with strike marine workers. The

employers' answer was dispatched by T.G. Plant, their chairman, but not

made public.

Return to the Museum's General Strike Page. |

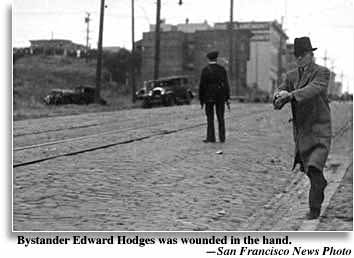

Police reinforcements scurried to the scene. Mounted officers rode into the

crowd, pounding away with their clubs. More police gunfire at random

toward the men surging down the hillside. A bystander grabbed his wrist in

pain; he was the first man shot.

Police reinforcements scurried to the scene. Mounted officers rode into the

crowd, pounding away with their clubs. More police gunfire at random

toward the men surging down the hillside. A bystander grabbed his wrist in

pain; he was the first man shot.