|

CORTES AND CALIFORNIA

|

|

|

Source

Brief History of California, Book 1 By Theodore H. Hittell The Stone Educational Company San Francisco 1898

|

When Hernando Cortes conquered Mexico in 1521, he entertained the same idea that he was merely upon the threshold of India. When he found gold and silver in not inconsiderable quantities among the Aztecs, he felt justified in his belief in the greater wealth and barbaric splendor of the unknown regions beyond. And he was still more confirmed in this belief by a report, brought him by one of his lieutenants, named Gonzalo de Sandoval, in 1524, about an island lying at a distance of ten days journey from the ocean coast west of Mexico, which was said to be inhabited by women only and to be very rich in pearls and gold. This strange story-which constitutes the first account of California that can be found in the old records – though it may be doubtful whether Cortes credited it in all its particulars, excited his imagination to such a degree that he spent the next thirteen years of his life and almost all his fortune in building ships and sending expeditions to search out the supposed wonderful island, and in collecting and finally leading a little army, and going in person to take possession of it.

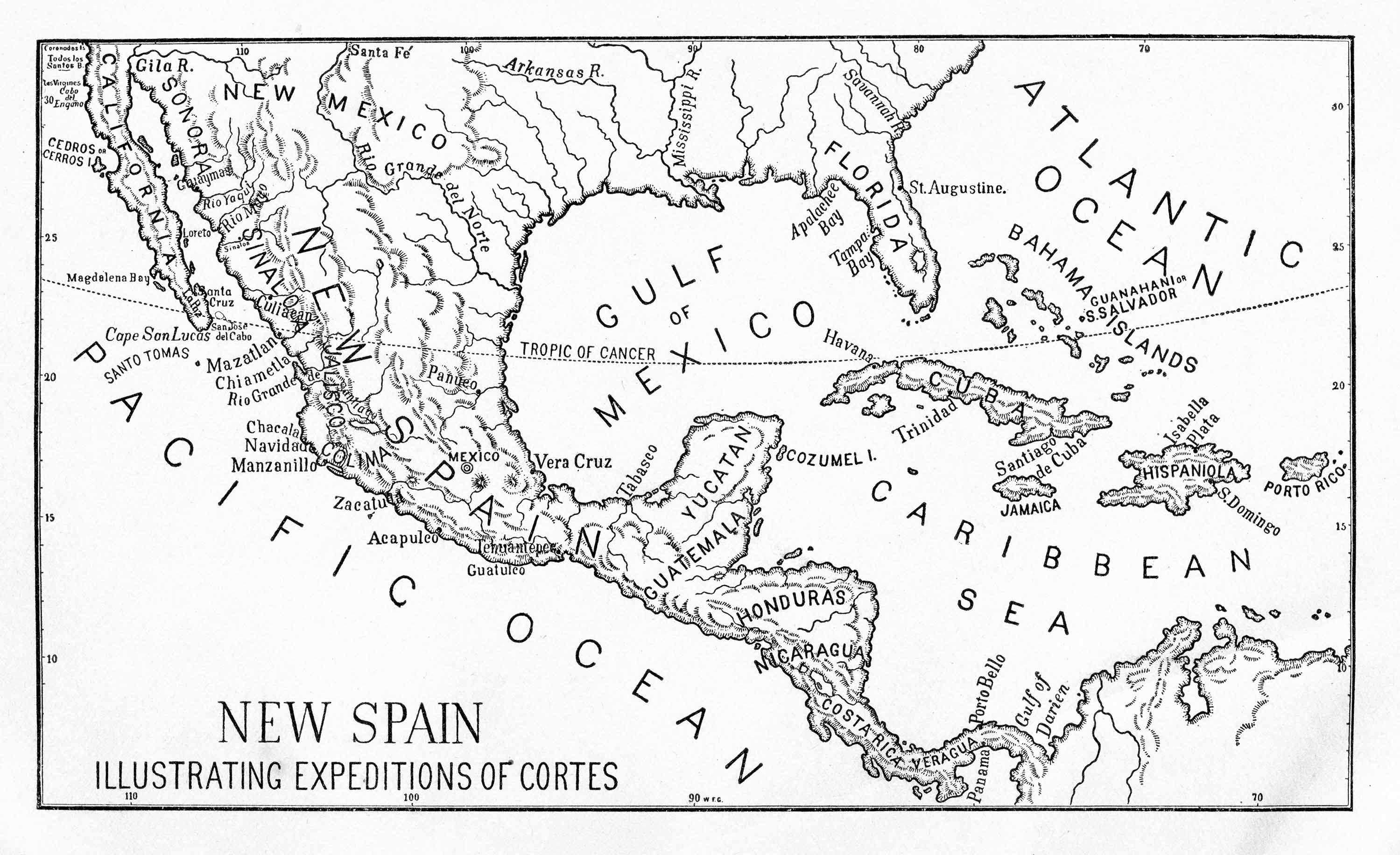

The first of Cortes' ships that steered in the direction of California was placed in charge of Pedro Nunez Maldonado. It sailed from Zacatula on the Pacific in 1528 and advanced as far as the Santiago River in Jalisco. Cortes next, in 1532, sent two ships, one in charge of Diego Hurtado de Mendoza and the other in that of Juan de Mazuela. They

sailed from Acapulco and proceeded up along the coast as far as the mouth of the Mayo river, where a mutiny occurred, and Mazuela's ship was sent back with the mutineers. Hurtado proceeded further north and reached the mouth of the Yaqui river, where he and his men were killed by the Indians. The mutineers in the same fate on their way back along the coast of Jalisco. Notwithstanding these misfortunes, Cortes sent two new vessels from Tehuantepec in 1533. One was in charge of Diego Becerra de Mendoza and the other in that of Hernando de Grixalva. They sailed only a short distance together and then separated. Grixalva ran out some distance into the ocean and discovered the island of Santo Tomas, a couple of hundred miles south of Cape San Lucas, but found that it contained neither wealth nor human inhabitants. Becerra de Mendoza, on the other hand, ran up the coast as far as Jalisco, Mazuela's ship met

where a second mutiny broke out, which was headed by Fortuno Ximenez, the chief pilot of the ship. The mutineers, after killing Becerra, compelled his friends to go ashore and then sailed with the vessel directly away from the ill-fated coast. After being out of sight of land for a number of days, they finally discovered what they supposed to be an island, but was in fact the place now known as La Paz in Lower California. And thus it was that Cortes mutinous pilot, Fortuiio Ximenez, in 1534, became the discoverer of California.

Ximenez, as appears, disembarked on the supposed island and was there killed, with twenty of his companions, by the Indians. But a sufficient number of the sailors remained to navigate the vessel back to Jalisco, where they gave information of the discovery that had been made, and added that the supposed island was well peopled and that its coasts abounded in pearls. Cortes, as soon as he heard this report, notwithstlanding the great losses he had sustained, immediately fitted out another expedition consisting of three ships, which sailed from Tehuantepec, and some four hundred persons with whom he embarked on the vessels at Chiametla in Jalisco; and, to insure faithful service, he put himself at the head of the adventurers. In May, 1535, he landed at the same place where Ximenez had been killed, and gave to it the name of Santa Cruz. He at once began investigations about the country; but it proved to be the most barren and forbidding he had ever beheld. There were a few natives, but they were the poorest, most abject, most degraded human creatures he had ever met There were also some pearls along the shore, but not a particle of gold or silver or other wealth was to be seen.

In a very short time, on account of the failure of those whom he had ordered to follow him with further stores, his provisions ran low. His people began to suffer; and, when they began to suffer, they began to complain. He tried to console them with the promise of better times to come. He said that they had unfortunately struck a rough part of the country, but that further on they would undoubtedly find wealth and splendor enough to satisfy their most ardent longings. He also, as there is reason to believe, called their attention to the statements of a noted romance, published in Spain in 1510, affirming the existence of an island, called California, which lay "on the right hand of the Indies, very near to the terrestrial paradise." It was said to be surrounded by steep rocks and almost inaccessible cliffs and to be peopled by women who lived the life of Amazons. These women were represented as of great bodily strength and courage; and it was added that their arms, as well as the trappings of the wild beasts, which they rode on their warlike expeditions, were entirely of gold-that being the only metal the island produced.

This story, which it will be noticed was in substance the same as that told by Sandoval in 1524, Cortes seems to have repeated to his suffering followers for the purpose of cheering up their spirits. He tried to make them believe that the barren rocks and cliffs they saw around them were only the surroundings of the wonderful island thus represented as lying close to the Indies and near the terrestrial paradise. However this may have been, it is certain that he supposed

the country to be an island and that he gave to it the name, previously used in the romance referred to, of California. He himself believed it rich, and he made many attempts to explore it. But as far as he was able to penetrate, it continued to present the same rough and forbidding features. It was, in that part of it, a country of rocks and cliffs; its scant vegetation mostly thorny; its inhabitants poor, naked

savages. There was no wealth and no indications of barbaric splendor. Under the circumstances, Cortes, in the beginning of 1537, feeling himself obliged to give up further search, returned, with most of his people, to Mexico; and he was soon afterwards followed by the remainder. And thus ended the first attempt of the Spaniards to settle

California.

Source

Brief History of California, Book 1

By Theodore H. Hittell

The Stone Educational Company

San Francisco 1898

|

|