|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Samuel Dickson

The San Francisco part of this story came to me in bits, like the insignificant pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that have no particular import in themselves, but which, when placed in their proper positions in the over-

The San Francisco part of this story came to me in bits, like the insignificant pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that have no particular import in themselves, but which, when placed in their proper positions in the over-I found the first small piece in a book on old San Francisco. The year was 1878, and the item tells of the home of Joseph Duncan, a suave and cultured gentleman who was a cashier of the Bank of California and whose fortune crashed with William Ralston's. He was known as a connoisseur of the arts, and was often asked to select paintings and marbles for the palaces of his friends who knew little about them. His own home at Geary and Taylor Streets held many treasures. At one corner now stands a drugstore, at another a grocery and fruit store, at another the Bellevue Hotel, and the Clift Hotel on the fourth. In 1878 Joseph Duncan's home of art treasures occupied one of those corners. I'm under the impression that it stood at the northwest corner where the drugstore now stands. But it was shortly, after 1878 that the home was broken up and scandal and divorce resulted. Mrs. Duncan was a virtuous, high-

The Duncans had several children and very little money, and that made the scandal more tragic. Joseph Duncan had been a brute and a scoundrel, and Mrs. Duncan virtuously spent many years telling the children what a scoundrel their father was. However, one of the children mat Papa some years later and found him a charming, cultured gentleman of appealing personality. But that all came later.

The second small piece in the jigsaw puzzle was a personal experience of mine that happened a few months less than fifty years after the scandal at the corner of Geary and Taylor Streets. It was the summer of 1927. I had been invited to a soiree– no other word describes the function– in a home out on Pacific Avenue. There were long-

Ina Coolbrith, the poet laureate of California, was very old. That was last year of her long life. She was a gentle, sweet-

Ina Coolbrith, the poet laureate of California, was very old. That was last year of her long life. She was a gentle, sweet-

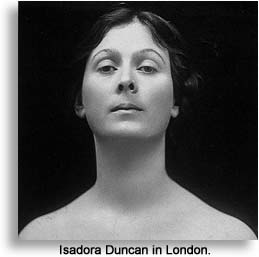

Her friends had been Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Charles Warren Stoddard, Robert Louis Stevenson, Joaquin Miller, Harr Wagner, and Jack London, and they all had loved her. She told me about them quite simply as though their love was her rightful heritage. And there was one other. He was a poet, a dreamer, a musician, and a connoisseur of the arts! She had been the one great love of his life. His name was Joseph Duncan. Joseph Duncan was long since dead and she, the poet laureate, went on, dreaming in the memories of the departed years. Joseph Duncan! He had been so gentle, so great an idealist, and so fine a poet! What if he was a cashier in a bank; even a bank cashier could dream of sonnets. But he was dead and the pages of his story were closed. Yet it was not really ended, for he lived on in his children. There were four of them, and Ina Coolbrith had learned to know and love one of them well. Her name was Isadora Duncan.

As I stated before, that is the second bit in the pattern of the jigsaw puzzle. Now, before we come to the story of Isadora Duncan—

He was led across the stage, his steps faltering, as the blind should be led. But this wasn't acting; He was in fact blind, He was Raymond, one of children of Joseph Duncan.

There are the bits in the pattern. It was in Oakland, a few years after the scandal at Geary and Taylor Streets, that Ina Coolbrith met the child, Isadora. She came to the Oakland Public Library, as a few years later Jack London was to come, to ask the library lady, Miss Coolbrith, for a book to read. Just as Ina Coolbrith was to guide Jack London's reading some time later, so she guided and shaped the mind of the small daughter of Joseph Duncan.

Isadora was a quaint child, a strange mixture of practical common sense and worldly sophistication, and she was a dreamer like her father. The child loved poetry, beauty, and rhythm, and she hated reality. She was, in fact, a rebel. Her childhood had been an unhappy one. There was strife and divorce, with her mother's insistence that her father, Joseph, was a demon in human garb. Then there was her mother's disavowal of the religion in which she had been raised, and her espousal of the atheism of Robert Ingersoll. These were the unhealthy shapers of Isadora's childhood. Of course, when she eventually met her father, she found him a charming, lovable poet, and that heightened the confusion in her mind. Passing years tend to soften the intolerance of childhood, but Isadora Duncan never lost her contempt for the institution of marriage as she had seen it. When she was twelve years old she made a solemn vow that she would welcome love when it came, but she would never marry.

After the divorce, Mrs. Duncan found a small, drab home in Oakland for her brood of four children. The constant poverty in which they lived was softened by the wealth of poetry and music that Mrs. Duncan brought into the home, molding the lives of her small offspring. The four of them loved to sing, loved to play-

When she was fourteen years old, pupils, children of neighbors, came to her to be taught to dance. The Oakland classes grew and then there were classes across the bay in San Francisco. Every day Isadora and her sister, Elizabeth, took the ferryboat to San Francisco and then walked from the Ferry building to Sutter and Van Ness Avenue. There, in the old home they had rented—

But Isadora didn't like poverty and she didn't like restrictions. There were distant horizons awaiting her. She read about them in her books, the faraway places that call to all imbued with the creative instinct. Any place would do as long as it was "away." She induced her mother to take her to Chicago. What matter that the family purse was, as always, almost empty? Funds were found and, armed with a wealth of enthusiasm, mother and daughter started out.

The Eastern theatrical managers saw the girl dance, praised her, told her it was all very lovely. But, after all, that wasn't the accepted way to dance; it wasn't the way of the theater. No, it would never do. She'd better go home to San Francisco and be a schoolteacher! Their funds were gone, so they pawned their jewelry. They ripped a bit of old Irish lace from Isadora's dress and sold it. Finally, starvation, not a threat but an actuality, faced them, and then Isadora received an engagement. At last, she was to dance– to dance in a music hall. In a fogged atmosphere of stale beer and tobacco smoke the girl appeared, a breath of ancient Greece. Her audience chewed on its cigars. They found it all a little uncomfortable. This certainly wasn't what they'd come to see! In short, they wished she'd get through so the next act could appear.

But in the audience one night sat a dreamer like herself. He was Augustin Daly, the theatrical producer. He saw what none of the others had seen– the vision, the ideal, and the dream behind the dancing of the girl. He cast her as one of Titania's dancing fairies in his production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. He gave her small part in pantomimes. Perhaps she couldn't force her audience to understand the beauty of simplicity, but at least this gave her the opportunity to dance, and to eat.

Her brothers and sisters were sent for, and the family settled to New York. One night Isadora danced to the music of Ethelbert Nevin; Nevin was in the audience, entranced. He arranged for concerts for her and suddenly blasé New York. hailed a new star, a child with the wisdom of the ages and the simple innocence of the sheep that grazed on the Athenian hills. Society accepted her. She danced for the four hundred in Newport's exclusive salons. They made much of her, but just as swiftly they dropped her. And again the family purse was empty.

Once again the lodestone of distant horizons beckoned. What did it matter that the family had no money? They would go to London. After Isadora had borrowed right and left from her former friends of Newport society, the Duncans sailed.

In London, a few engagements brought a few dollars, but the few dollars weren't enough to fill the young hungry stomachs. Then one night Isadora and one of her brothers were dancing in their Grecian veils in the small garden of a tiny house in Kensington Gardens. They danced by the light of the stars and their only audience was their own shadows. Quite unexpectedly, a beautiful lady came and stood watching them and was amazed. When they had finished their dance she swooped down upon them and took them to her own home. She was Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the idol of the London stage. She played for them and they danced for her; she. sobbed dramatic tears, and introduced them to London society.

The meeting with Mrs. Pat Campbell was the turning point in the story of Isadora Duncan. Mrs. Campbell introduced them to London society acclaimed them, and British royalty honored them. Life became busy, hectic, and full to overflowing with triumphs– and setbacks, Duncan, the dancer, had arrived, but the girl, Isadora, was still a rebel against customs and traditions– and marriage.

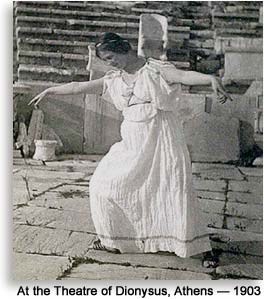

She danced in Paris and was cheered. she danced in Berlin, and the art-

In the Athenian hills Isadora gathered a class of small Grecian boys about her. She taught them the dances of ancient Byzantium, as well as Greek choruses and songs. bare-

Vienna took her to its gay heart, and success and wealth returned. But now Isadora Duncan learned that life without the fullness of love was incomplete. Then, in Berlin, in 1905, she met Gordon Craig, the colorful, handsome, glamorous son of Ellen Terry. This was the great love; this was life at its highest. The world sighed, and giggled, and was delighted. Isadora was perfectly happy. A baby was born, and they named her Deirdre. Isadora adored her.

New friends came to join the strange household. Eleanor Duse, her life shattered by the tragedy of her romance with D'Annunzio, took them to Italy to aid her in the production of an Ibsen drama. Isadora danced her dances of the Athenian hills in Rome. But now a new ambition and dream was born. She would train choruses, and build her greatest ballet around the music of Beethoven's immortal Ninth Symphony.

She came to the United States and danced to the music of Walter Damrosch's orchestra. America was shocked, and delighted. Of course, everyone had a body, but one didn't acknowledge the fact. Even modest ankles weren't to be exposed. That nonsense was ended by an edict from no less a wielder of strong opinion than Teddy Roosevelt. "Isadora Duncan," he proclaimed, "seems to me as innocent as a child dancing through the garden in the morning sunshine and picking the beautiful flowers of her fantasy." So the master politician became poet, and Isadora danced and was forgiven her sins.

She built a school where she taught young girls the beauty of the dance. She was the priestess of the dance, and in that role did more to return it to its ancient glory than any other single man or woman in the world's history of terpsichore.

Then, one night in Paris, Isadora Duncan danced to the haunting melody of Chopin's "Funeral March," and a vision of tragedy came to her. She danced with eyes closed and saw her two children threatened by evil. She danced as though in a trance, and her audience sat, thrilled, chilled, and breathless. It was terrible and it was beautiful. A few days passed and the father of her son stood before her. His lips were dry and his eyes were haggard. He told of the death of her two children.

Life was dead; dreams were dead; the world was empty. Isadora Duncan, the rebel, had won her rebellion and lost all that was worth the fight. She felt she would never dance again. But she did dance. In her tragedy she had become a giantess, and life does not or cannot stand still. She won new triumphs, found new loves, and achieved new furors. She faced new tragedy in 1914 when, under the shadow of the dawn of the first World War, another baby was born—dead. Still she danced, and still she continued to teach her girls. She danced her Ninth Symphony to an audience that sat as though in the presence of a creature divine. Her greatest creative dream had become a reality.

Isadora Duncan, the little girl of Geary and Taylor Streets in San Francisco, died in 1927. A veil caught in the wheel of her automobile. There was the grinding of brakes—and then darkness. She died tragically, horribly, and the world was upset for a few hours and then went about its business. But those who had loved her and who knew her dream of beauty mourned her passing of a human creature who had been an honest builder of dreams. She had done more for the art of the dance than any other man or woman in history. And above all else, she had been the honest daughter of her poet father.

Budd Heyde can be heard on this 78-RPM promotional phonograph recording made for W. and J. Sloane sometime during the late-1940s.

Isadora Duncan photograph by Arnold Genthe

Samuel Dickson was a prolific magazine writer in the 1920's and early 30's, and became an NBC feature writer in the late 1930's. He wrote the NBC-KPO/KNBC series "This is Your Home," sponsored by W. and J. Sloane, then one of San Francisco's leading furniture stores. The series was narrated by NBC-KPO/KNBC (now KNBR) announcer Budd Heyde, and broadcast during the late 1940's and into the 1950's at 10:30 Sunday mornings. This Isadora Duncan chapter was originally one of the KPO/KNBC radio scripts, later printed in "San Francisco Kaleidoscope," Stanford University Press, 1949.

Samuel Dickson was a prolific magazine writer in the 1920's and early 30's, and became an NBC feature writer in the late 1930's. He wrote the NBC-KPO/KNBC series "This is Your Home," sponsored by W. and J. Sloane, then one of San Francisco's leading furniture stores. The series was narrated by NBC-KPO/KNBC (now KNBR) announcer Budd Heyde, and broadcast during the late 1940's and into the 1950's at 10:30 Sunday mornings. This Isadora Duncan chapter was originally one of the KPO/KNBC radio scripts, later printed in "San Francisco Kaleidoscope," Stanford University Press, 1949.